identity through

objects

Volume I

The Nation

This project attempts to understand the shape of Bangladeshi identity through the curation of valuable objects in a historical location of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The aim of this thesis is to investigate identity and culture through the lens of stolen objects and objects of the future that meaningfully resonate with the identities and culture of Bangladesh, a fragmented land and identity that has developed through colonization, religious suppression, dominion, and war among other forces that have shaped it into the modern Bangladesh we know today. The current National Museum of Bangladesh fails at doing this, instead housing political propaganda, fetishizing Bangladesh for a foreign gaze and lacking appropriate curation of objects that hold meaningful cultural and historical values to our identities. The museum will be critiqued and studied on its programs, its vision, its site and the architectural strategies implemented to represent Bangladeshi identity.

Insight

This project, in its essence, is an exploration of identity on two different scales: the macro and the micro. The nation and the self. As well as the places where the micro and macro intersect. I used this form of site analysis and boiled it down to its essence to create objects, the largest of which is the museum itself.

As such, the museum architecturally, lacking in any relevant historical context, is almost an insult to its surroundings, especially by alienating the rest of this important historical space of Shahbag by placing large boundary walls all around. This is what I felt when I was able to visit the museum in person in 2020. The museum failed to represent the history, culture, and stories of my people that date back thousands of years.

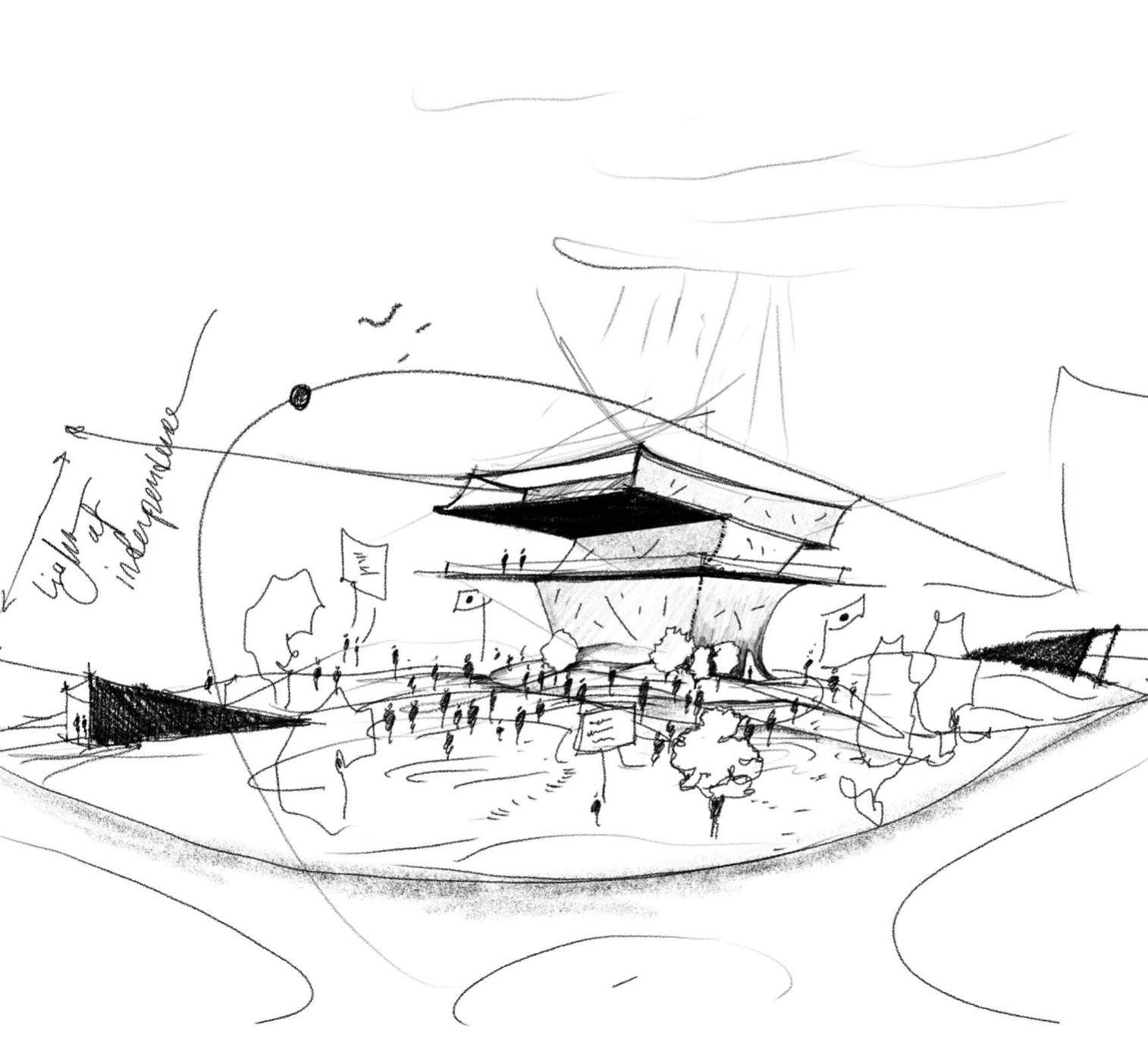

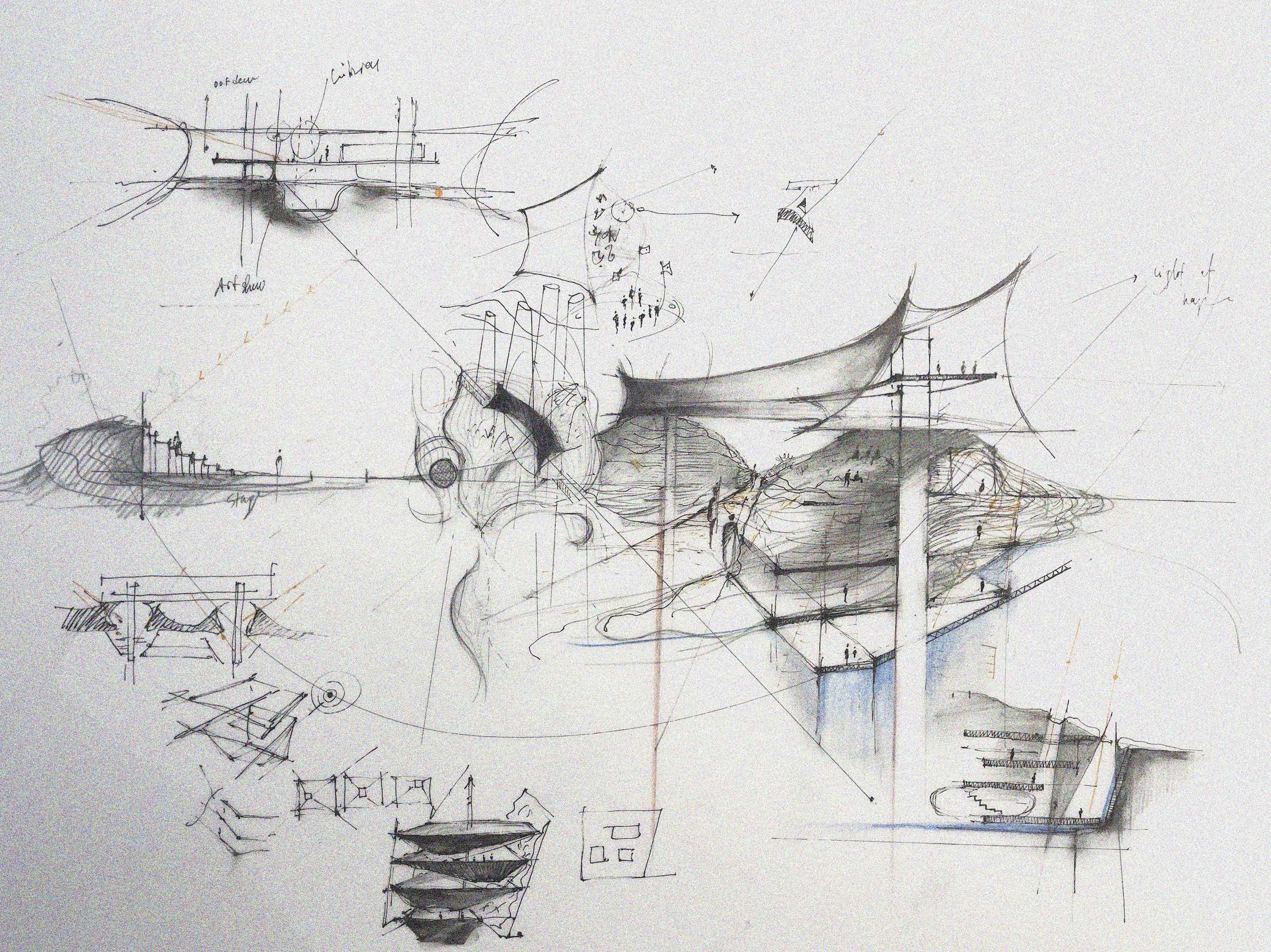

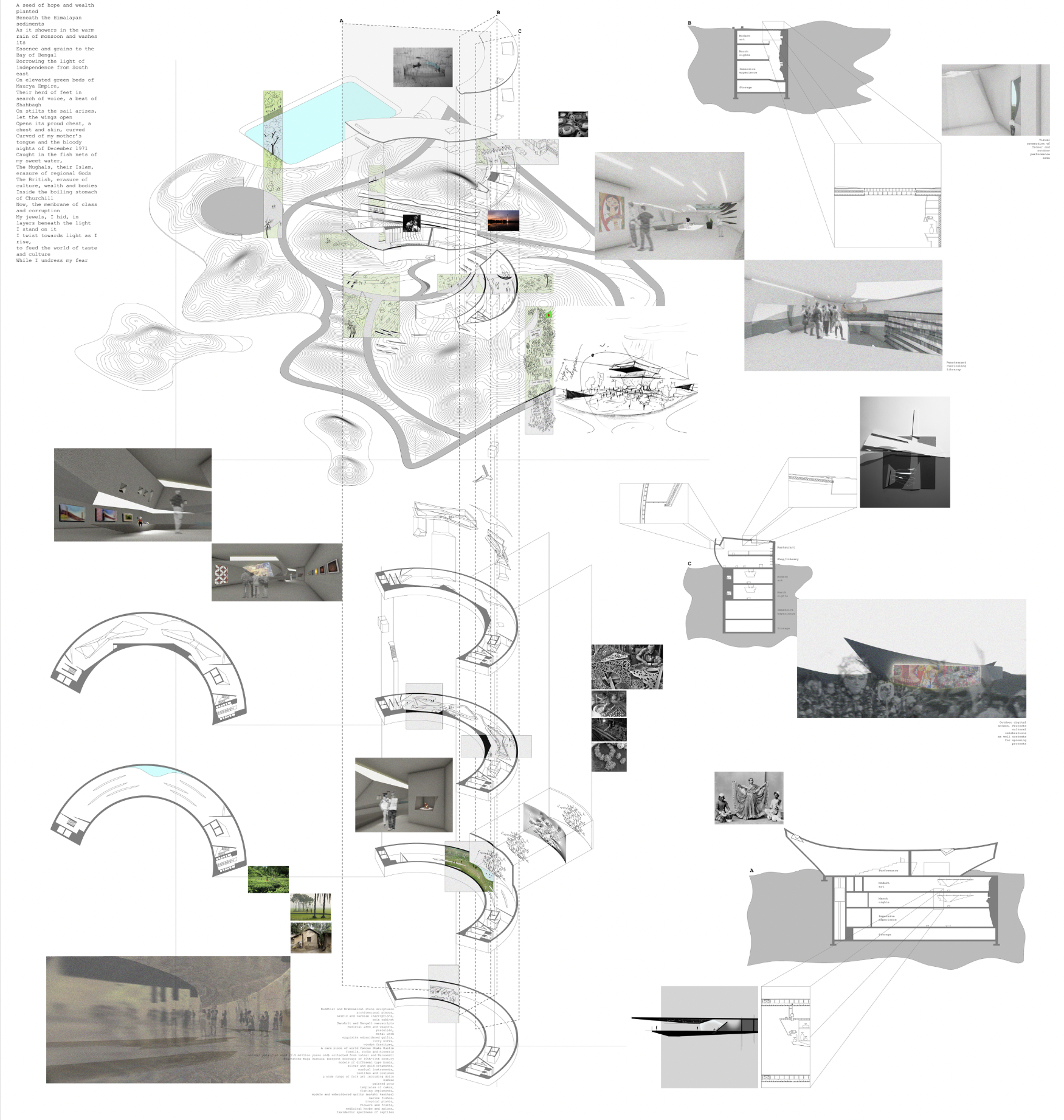

As a Bangladeshi architect and individual, I wanted to redesign the museum into a space that felt truly representative of us as a nation. I looked at the museum itself as an object that reflects the different facets of Bangladeshi identity. This happens in a variety of ways. One example of this is the landscaping. The way the ground is manipulated borrows ideas and shapes from the ruins of Mahastangarh in the North of Bangladesh. Mahastangarh is the oldest archaeological site found thus far in Bangladesh, dating back to 300 BCE, dating the Bengali civilization back to several thousands of years. The key formal element of this prehistoric site is the way it was built in various layers, delineated by raised walls and ramparts. This is something I wanted to reflect in my landscaping around the museum grounds, while also allowing it to serve a function: that of serving as a public space for gathering and protests. The high boundary walls are removed to create fluidity of movement with the museum grounds blending into the street and vice versa, inviting the public in. The various elevations in the landscaping allow for some parts to become podiums, others to become a stage, some places to offer seating for protestors. Music, theatre, and poetry recitation among other performing arts is also a crucial part of our culture, which has bred important, globally-known figures such as Tagore. This is also integrated into the landscaping through a large outdoor plaza where performances can be held.

Similarly to the landscaping, each aspect of the museum is designed meaningfully to represent our national identity.

It is done through a variety of lenses. For example: Landscape. Both the physical topography of the land, as well as the historical landscape, the layering of historical contexts that created our unique identity. Language is another lens, as it is an extremely important part of our culture, allowing us to be the third largest ethnolinguistic group in the world. Our language, Bangla, is something we also fought for during the Language Movement where we defied our Pakistani oppressor’ who wanted to erase our national identity by persecuting the official use of Bangla. Another lens would be material, the physical materials that make up our ecosystem like rain, mud, and the delta itself, Bangladesh being the largest delta in the world. I was also inspired by the lens of form and how we are attracted to a more organic way even of city-building, moving away from alignment and a grid system, as well as other forms like Mughal gardens, the brick kilns that dot our landscape. This, exploration of form as a lens for example, allowed me to settle on Mahastangarh as an inspiration for the landscaping of this project. Finally, I was inspired by the lens of complexity: the complexity of our history, our multiple colonizations, the density of our greenery even on the site of the museum, our 700 rivers, and even the intricacy of our handicrafts like filigree, mosaic, and woodwork.

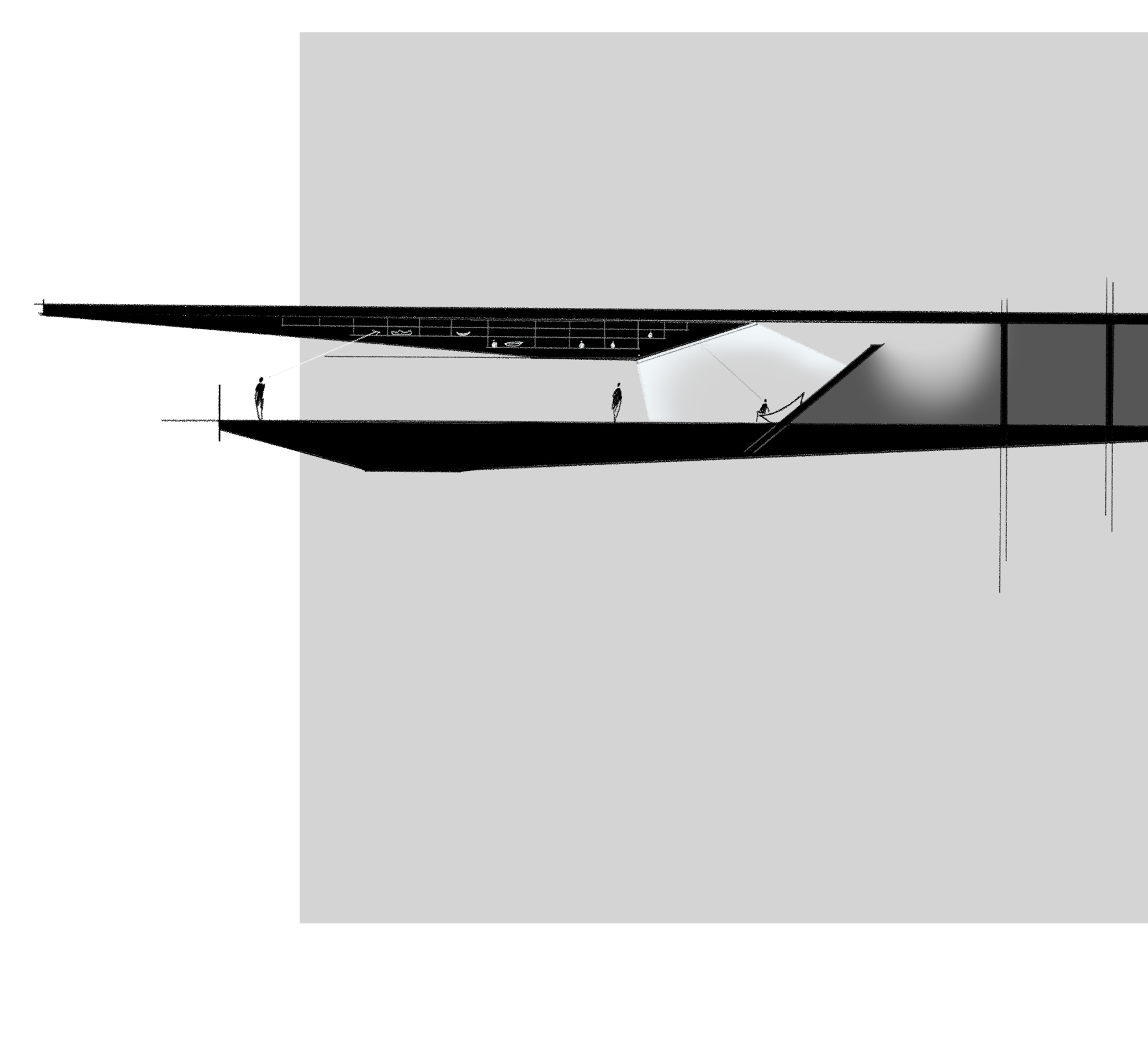

Going back to the lens of form, the shape of the museum is very much inspired by boats, another important part of a culture that is built on so many rivers like we are. Here, I’ve borrowed from my own memories of traveling by boat, especially when traveling between the capital and my hometown, which can only be reached by boat. I wanted to capture the essence of the crowded public ferry where you are unable to see past people to the outside. This is reflected in the way that when you enter the museum, you are fully inside it without much visual access to the outside world through windows. The only light that penetrates is that which comes from perforations in the form, which are meant to reflect the character of these public ferries, with their cracked bodies, messy and misplaced welding, and holes that have appeared over time. The physical building also tears up in the same way to allow light in. This journey through the river, physically and in essence, housed many memories for me. The topography of the landscape, if you look closely, also represents waves upon which the boats are placed, symbolically carrying the nation and its culture into a brighter future. This blending of my formative memories with that of a formal symbol like the boat that is of national cultural importance is another way the micro and the macro, the self and the nation, come together to inform the architecture of the museum.

The majority of the experiential programs of the museum is housed below ground. As the designer, my proposed circulation for visitors starts at the third floor, the bottom-most publicly accessible floor with the only other floor below being used primarily for the storage of artifacts, staff offices, and archives. This third floor introduces museum-goers to the natural environments and ecosystems of Bangladesh. Bangladesh has rich ecosystems filled with wildlife that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. The most famous of these is, of course, the Bengal tiger that lives in the Sundarbans, our mangrove forest to the south of the country that also happens to be the largest mangrove forest in the world and an ecological community brimming with life. Bangladesh also has six seasons, each with its own distinct characteristics like the Kalboishakhi storms that appear in the first month of the Bangladeshi new year and the kashful, or wild sugarcane grasses that grow up to three meters high and bloom mid-way through the year into feathery white tails, pictured often against the bright blue sky of that time of year. I want these images to be reflected through the experience of this floor that uses immersive display and cutting-edge projection mapping technology to engage the visitors in these natural environments.

Bangladeshis place strong emphasis on the natural bounties of our land and country. However, the way the museum tries to educate visitors about this right now feels extremely inadequate. During my visit to the museum in 2020, I was greeted by dusty bowls of fake vegetables and awfully taxidermied animals that tried, but failed, at capturing this. As a designer, I want to show Bangladeshis that the natural beauty of our land can indeed be captured through brand new technology, instead of resorting to fake models and dioramas, which fall short of being able to do so.

A floor above this, on the second floor, visitors would be better able to understand Bangladesh’s political and historical contexts. I want this to be able to narrow in, as well, on certain events that shaped the course of Bangladesh’s history. I propose humanizing the history through exhibits on topics such as our martyred intellectuals during our Liberation War, when Pakistani forces carried out a systemic killing of Bangladesh’s intellectual class.

Moving up, the first floor would be dedicated to the modern art of Bangladesh. Bangladesh has given birth to many seminal artists who shape the art and culture of our nation. This includes Jainul Abedeen who famously sketched scenes of the famines brought on by British colonizers to Ferdousi Priyabhashini who sculpted works about the abhorrent treatment of women during the Liberation War by the Pakistani army. The works of these artists add great texture and character to the culture of our nation and would be included in this first floor, along with rotating exhibits of new and upcoming Bangladeshi artists.

All three floors would be brought together by a wall that connects these different programs. During my visit in 2020, I was particularly shocked by the treatment of important artifacts and objects. In one room, hundreds of precious and invaluable sculptures dating back over 2,000 years, were placed on shaky plywood pedestals, or even leaned against the wall with nothing to protect them from being touched or prodded by children, and with thick layers of dust covering them. To return these artifacts to the place of respect they deserve, I would propose to house them within recesses and cutouts that are built into this connecting wall, protecting these artifacts from all sides while allowing them to be viewed. The pattern of these recesses, when viewed as a whole, would form the texture of batik fabric, a traditional technique of fabric dyeing, while the topography of the wall itself would be inspired by the North of Bangladesh from where most of these artifacts have been excavated.

This project, in its essence, is an exploration of identity on two different scales: the macro and the micro. The nation and the self. As well as the places where the micro and macro intersect. I used this form of site analysis and boiled it down to its essence to create objects, the largest of which is the museum itself.

The Bangladesh National Museum was built in the 70s by the architect, Robert C. Boghe, an American architect from Pennsylvania who knew little about Bangladesh. As you can imagine, his design was unable to capture Bangladesh’s national identity in its fullness. The museum itself is also located in an integral part of Dhaka City, Shahbag, which is the center of the city and located at a junction between two contrasting parts of the city: the Old Dhaka and the new and modern Dhaka. Shahbag is also home to some of the country’s most important institutions like Dhaka University, established in 1921 and known at one time as ‘the Oxford of the East,’ Dhaka Medical College, the High Court and the public library.

In short, Shahbag is filled with the rich history of Dhaka, holding remnants from the Mughal period to British colonization. Today, Shahbag square has become the main venue for celebrating various cultural festivals like the Bengali New Year. In the past few decades, Shahbag has also become the primary backdrop and origin of some of the country's largest political movements, playing key roles in transformational events like the Liberation War of 1971 when Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan. Today it is still where the people of the nation come together to hold protests, marches, and demonstrations, as protest and dissent continue to be a large part of our national identity.

As such, the museum architecturally, lacking in any relevant historical context, is almost an insult to its surroundings, especially by alienating the rest of this important historical space of Shahbag by placing large boundary walls all around. This is what I felt when I was able to visit the museum in person in 2020. The museum failed to represent the history, culture, and stories of my people that date back thousands of years.

As a Bangladeshi architect and individual, I wanted to redesign the museum into a space that felt truly representative of us as a nation. I looked at the museum itself as an object that reflects the different facets of Bangladeshi identity. This happens in a variety of ways. One example of this is the landscaping. The way the ground is manipulated borrows ideas and shapes from the ruins of Mahastangarh in the North of Bangladesh. Mahastangarh is the oldest archaeological site found thus far in Bangladesh, dating back to 300 BCE, dating the Bengali civilization back to several thousands of years. The key formal element of this prehistoric site is the way it was built in various layers, delineated by raised walls and ramparts. This is something I wanted to reflect in my landscaping around the museum grounds, while also allowing it to serve a function: that of serving as a public space for gathering and protests. The high boundary walls are removed to create fluidity of movement with the museum grounds blending into the street and vice versa, inviting the public in. The various elevations in the landscaping allow for some parts to become podiums, others to become a stage, some places to offer seating for protestors. Music, theatre, and poetry recitation among other performing arts is also a crucial part of our culture, which has bred important, globally-known figures such as Tagore. This is also integrated into the landscaping through a large outdoor plaza where performances can be held.

Similarly to the landscaping, each aspect of the museum is designed meaningfully to represent our national identity.

It is done through a variety of lenses. For example: Landscape. Both the physical topography of the land, as well as the historical landscape, the layering of historical contexts that created our unique identity. Language is another lens, as it is an extremely important part of our culture, allowing us to be the third largest ethnolinguistic group in the world. Our language, Bangla, is something we also fought for during the Language Movement where we defied our Pakistani oppressor’ who wanted to erase our national identity by persecuting the official use of Bangla. Another lens would be material, the physical materials that make up our ecosystem like rain, mud, and the delta itself, Bangladesh being the largest delta in the world. I was also inspired by the lens of form and how we are attracted to a more organic way even of city-building, moving away from alignment and a grid system, as well as other forms like Mughal gardens, the brick kilns that dot our landscape. This, exploration of form as a lens for example, allowed me to settle on Mahastangarh as an inspiration for the landscaping of this project. Finally, I was inspired by the lens of complexity: the complexity of our history, our multiple colonizations, the density of our greenery even on the site of the museum, our 700 rivers, and even the intricacy of our handicrafts like filigree, mosaic, and woodwork.

Going back to the lens of form, the shape of the museum is very much inspired by boats, another important part of a culture that is built on so many rivers like we are. Here, I’ve borrowed from my own memories of traveling by boat, especially when traveling between the capital and my hometown, which can only be reached by boat. I wanted to capture the essence of the crowded public ferry where you are unable to see past people to the outside. This is reflected in the way that when you enter the museum, you are fully inside it without much visual access to the outside world through windows. The only light that penetrates is that which comes from perforations in the form, which are meant to reflect the character of these public ferries, with their cracked bodies, messy and misplaced welding, and holes that have appeared over time. The physical building also tears up in the same way to allow light in. This journey through the river, physically and in essence, housed many memories for me. The topography of the landscape, if you look closely, also represents waves upon which the boats are placed, symbolically carrying the nation and its culture into a brighter future. This blending of my formative memories with that of a formal symbol like the boat that is of national cultural importance is another way the micro and the macro, the self and the nation, come together to inform the architecture of the museum.

The majority of the experiential programs of the museum is housed below ground. As the designer, my proposed circulation for visitors starts at the third floor, the bottom-most publicly accessible floor with the only other floor below being used primarily for the storage of artifacts, staff offices, and archives. This third floor introduces museum-goers to the natural environments and ecosystems of Bangladesh. Bangladesh has rich ecosystems filled with wildlife that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. The most famous of these is, of course, the Bengal tiger that lives in the Sundarbans, our mangrove forest to the south of the country that also happens to be the largest mangrove forest in the world and an ecological community brimming with life. Bangladesh also has six seasons, each with its own distinct characteristics like the Kalboishakhi storms that appear in the first month of the Bangladeshi new year and the kashful, or wild sugarcane grasses that grow up to three meters high and bloom mid-way through the year into feathery white tails, pictured often against the bright blue sky of that time of year. I want these images to be reflected through the experience of this floor that uses immersive display and cutting-edge projection mapping technology to engage the visitors in these natural environments.

Bangladeshis place strong emphasis on the natural bounties of our land and country. However, the way the museum tries to educate visitors about this right now feels extremely inadequate. During my visit to the museum in 2020, I was greeted by dusty bowls of fake vegetables and awfully taxidermied animals that tried, but failed, at capturing this. As a designer, I want to show Bangladeshis that the natural beauty of our land can indeed be captured through brand new technology, instead of resorting to fake models and dioramas, which fall short of being able to do so.

A floor above this, on the second floor, visitors would be better able to understand Bangladesh’s political and historical contexts. I want this to be able to narrow in, as well, on certain events that shaped the course of Bangladesh’s history. I propose humanizing the history through exhibits on topics such as our martyred intellectuals during our Liberation War, when Pakistani forces carried out a systemic killing of Bangladesh’s intellectual class.

Moving up, the first floor would be dedicated to the modern art of Bangladesh. Bangladesh has given birth to many seminal artists who shape the art and culture of our nation. This includes Jainul Abedeen who famously sketched scenes of the famines brought on by British colonizers to Ferdousi Priyabhashini who sculpted works about the abhorrent treatment of women during the Liberation War by the Pakistani army. The works of these artists add great texture and character to the culture of our nation and would be included in this first floor, along with rotating exhibits of new and upcoming Bangladeshi artists.

All three floors would be brought together by a wall that connects these different programs. During my visit in 2020, I was particularly shocked by the treatment of important artifacts and objects. In one room, hundreds of precious and invaluable sculptures dating back over 2,000 years, were placed on shaky plywood pedestals, or even leaned against the wall with nothing to protect them from being touched or prodded by children, and with thick layers of dust covering them. To return these artifacts to the place of respect they deserve, I would propose to house them within recesses and cutouts that are built into this connecting wall, protecting these artifacts from all sides while allowing them to be viewed. The pattern of these recesses, when viewed as a whole, would form the texture of batik fabric, a traditional technique of fabric dyeing, while the topography of the wall itself would be inspired by the North of Bangladesh from where most of these artifacts have been excavated.

Site

![]()

![]()

Visuals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Identity through

Objects

Volume II

The Self

Objects show. May, 2023

Eid-Gha

pine. stainless steel. two ft

As early as the sun, we washed

dressed as our mothers wanted

the new smell of cotton

hundreds on the streets

bowing like the fresh notes

to Allah we prayed

bare feet on wool, the geometry of Makkah

the soft grass so delicate

so dark but the awakening of rose water

warm water and chaos to be cleaned

back in school, we lined up

with faith we pierced the ground

allowed the line of light

to sing our soul

Ears

jewellery. thai-gold

My mother’s brother

squinted.

fat and fair, showered in gold

his gift from head to toe

in Arabic scripture

with colour came demons

stolen, sold, taken

nights of fear and an empty liver

she did not trust

but now she has it forever

hung from a porcelin wall

Space

Concrete. one ft

Ascending upon request

milk in glass

some sweet mushrooms with

fresh spring sprouts

days of mist and night of stars

two boxes

one selflessness

one with meals

both with silence

looking down to cold rocks

the wild boars marked their way

at sight we could only watch clouds

while the whales flew

Ascending upon request

milk in glass

some sweet mushrooms with

fresh spring sprouts

days of mist and night of stars

two boxes

one selflessness

one with meals

both with silence

looking down to cold rocks

the wild boars marked their way

at sight we could only watch clouds

while the whales flew

The room

pine. stainless steel. one ft

At last I captured

the time of hair and its strength

the time of seasons

through that window appeared all Gods

the shivering cold floors

but sat tight

when in summer we hung bracelets of yarn

the rotting walls of shine

it was us and steel

the hail and tears

Sugar

Concrete. eight inch

Every dusk a grain of sugar-rock

hidden beneath her pillow

children chewing, adults shaming

her favourite grandson

with her muslin, she wiped

Trees of love

pine. stainless steel. one ft

My fat mother sweating her pain

her blue veins all bulged

from carriages to walking

carrying a pile

we rested hugging the leaves

it’s 3 pm now

too hot, too thristy

she wipes her tears with her saari

she shares not to worry

she shares if we were

unlucky

My fat mother sweating her pain

her blue veins all bulged

from carriages to walking

carrying a pile

we rested hugging the leaves

it’s 3 pm now

too hot, too thristy

she wipes her tears with her saari

she shares not to worry

she shares if we were

unlucky

Red

Concrete. one ft

It was cracked but cold

so we both sat

we stare at the water, or

does it stare at us

we think

we laugh

the pile of clothes as green as the leaves

the candy so sweet

sweet sun, bathing in sweat

she almost stole the pile

Skin

pine. stainless steel. nine inch

Carrying the “wrong” skin

while they conquer

remain illiterate but invaluble

so here it is

use the teeth

scrape my skin

scrape your skin

lets walk on our hearts and soul

freeing our inner flesh

Paan

Concrete. nine inch

The river brought leaves

fresh leaves of rocks

plaster with maroon cream

five times a day

crimson filled mouth

dusty pure silver hands

a warm baby between pillows

filled cheeks

sound of grinding grains

sound of chewing

Weight

pine. stainless steel. eight inch

So heavy through breeze

torn streched silk

closed at both doors

a tunnel of nutrients

at birth they chopped

the angels on sides

their noticeable arrival

only to pick green berries

So heavy through breeze

torn streched silk

closed at both doors

a tunnel of nutrients

at birth they chopped

the angels on sides

their noticeable arrival

only to pick green berries

Lineage

Concrete.

From soft to hearts

from wealth to buried gold

from name to honour

giving and hearing in motion

motion of falling

falling with drops

drops aggressively melting

melting and hardening

hardened souls

souls of greed

the child parts in two

with light it’s warmed

it melts into forms

it forms back as one

from wealth to buried gold

from name to honour

giving and hearing in motion

motion of falling

falling with drops

drops aggressively melting

melting and hardening

hardened souls

souls of greed

the child parts in two

with light it’s warmed

it melts into forms

it forms back as one

other projects

2023

Identity through objects

cityscape

2022

first nation space

MEG Shop

2021

housing project16

alberto campo

2020

ny wellness centrefour legs

mars

cabin

coast

2019

thai wellness centrehouse of memories

office (completed)

dubai

2018

sreepurfor lover

a talk

2017

space of flow form